image credit: laundrybear.com

A Mortician’s Tale is the quiet, meditative debut of Toronto-based Laundry Bear Games. Released last month, the game takes you through the workday of a recently-graduated mortician named Charlie as she checks emails, prepares bodies for viewing and cremation, and attends services at the Rose And Daughters Funeral Home. “The interactivity of video games makes them the perfect medium to explore topics like death, grief, and mortality,” the game’s co-creator and designer, Gabby DaRienzo, tells me. “As opposed to a medium like film or music, where someone can witness these topics, video games encourage players to interact with them directly.”

And interact you do: in the hour or so it takes to play A Mortician’s Tale — available for Mac and PC through indie distributor Steam — I’ve learned to cremate, embalm, and even make difficult decisions when a family’s wishes counteract those of the deceased, who did not leave a will.

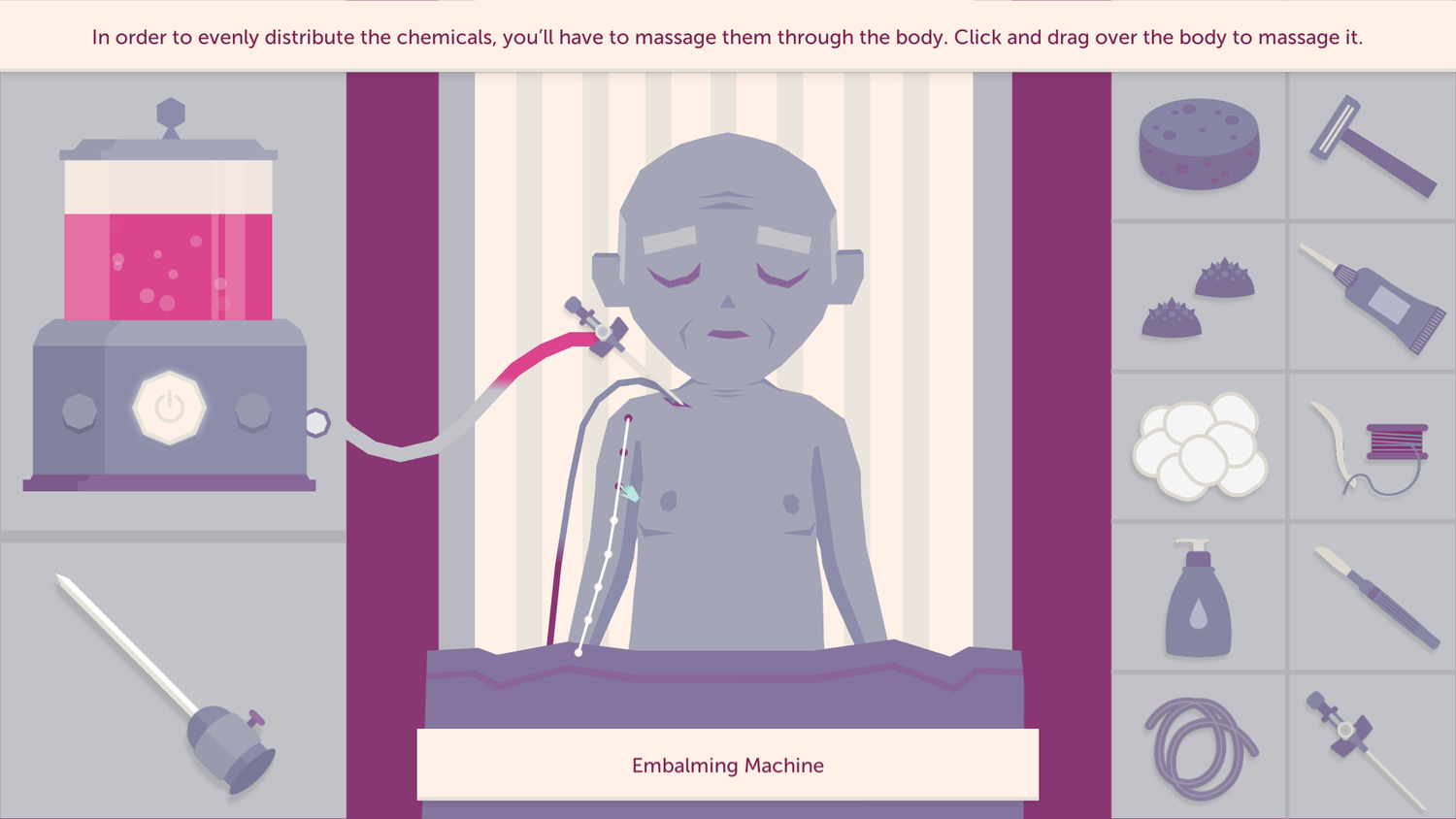

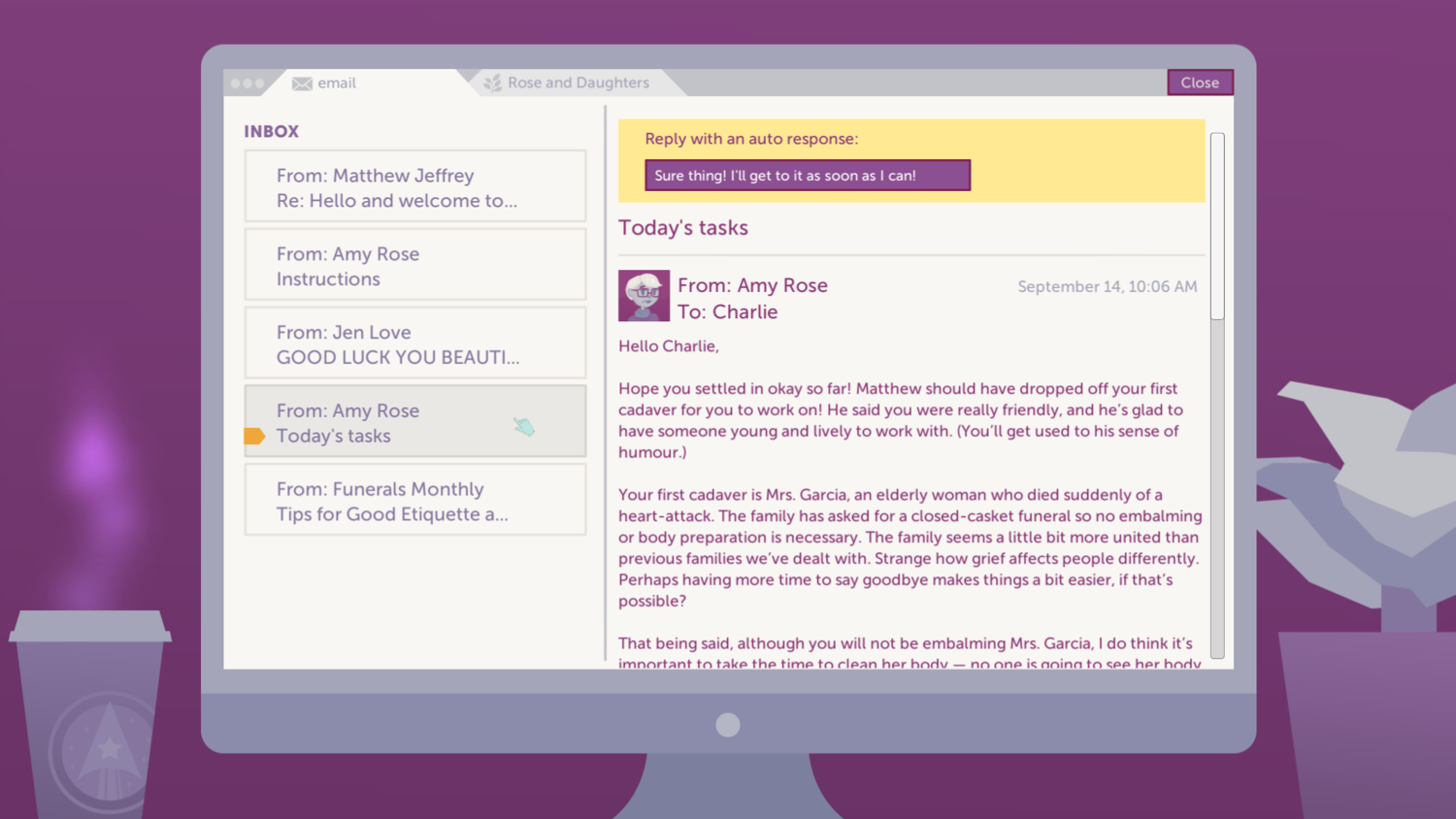

Working with the bodies is both unapologetically true and yet not designed to shock the way similar scenes might play out in a medical TV show. I fill mouths with cotton balls and sew the lips, placing spiked caps under eyelids to give the appearance of round, lifelike eyes. I place a cannula — a tube used to administer medicine, drain fluid, or insert a surgical instrument — into the carotid artery and turn on the embalming machine, massaging the body so everything is distributed evenly.

While this is fascinating, it’s the quieter moments I really love. I admit that games, partly for the interaction DaRienzo lauds, are not my favorite pastime — and when they are, I bend the rules. I ignore quests in favor of wandering through people’s homes, looking at their furnishings. I revisit my favorite NPCs, or non-player characters, instead of fighting monsters.

A Mortician’s Tale, to my delight, allows me to look through Charlie’s email inbox, which is filled not only with messages from her boss about what’s needed to do that day but with missives from her best friend, who just got a job at a pathology museum, and an industry newsletter, which is catnip for people like me who lived in the Lord of the Rings appendices rather than its chapters.

“The newsletter came about because there were many death-related topics we wanted to talk about in the game but couldn’t find good places to fit them,” DaRienzo explains. Green burials, aquamation — a cremation-like disposition method using water, which just became legal in California — and LGBTQ rights are some of the issues discussed in the newsletters, which help paint a fuller portrait of why conversations about death are so crucial. “While we cover a lot of death-related topics in the game, there are certain topics that closely resonate with our team and our team’s experiences, and we wanted to make sure we included those. We are a team mostly made up of queer women, so discussing LGBTQ rights after death was hugely important to us,” DaRienzo says.

A Mortician’s Tale’s main conflict is not a cremated body exploding due to a left-in pacemaker, or a disagreement with one of the families. Instead, it’s with the buyout of Rose And Daughters by a funeral industry conglomerate, which quickly replaces the mom-and-pop home’s family-tailored service to a faceless upsell model. This discrepancy is perhaps most clear in another quiet moment. Often, a second tab is open in Charlie’s browser. It could be a fully-functional ingame version of ghostly Minesweeper but after the buyout, it’s the funeral home’s new website.

The difference is jarring: prices have been entirely removed, and information is vague rather than helpful. Those of us who have ever had to make funeral arrangements know this isn’t hyperbole, but a common tactic. Watching Charlie receive nastygrams from her new boss for not upselling to families is another nail in the coffin. For some people, death is just business.

I won’t spoil the ending for you, but it’s in line with the rest of the gaming experience, which I found both informative and meaningful. I ask DaRienzo about the pace of the game, curious if others enjoyed the email exchanges and newsletters the way I did, or if players were expecting more corpse-time. “We knew we wanted to develop a game that recreates the experience of being a funeral director, and so we chose mechanics to reinforce that narrative,” she replies, referencing the amount of reading and slow, repetitive, and almost meditative tasks Charlie performs daily. “We’ve gotten a few negative responses from people who expected the game to be more of a fast-paced Diner Dash-like or business tycoon game, but neither of those were games we wanted to make — plus, those mechanics definitely don’t reinforce our game’s death positive themes.”

Death positivity is, after all, one of DaRienzo’s biggest inspirations in making the game, which initially originated as a simple pixel art prototype called Mortuary Simulator. When I was a kid, a girl in my grade and her mother died in a really tragic way,” DaRienzo tells me. “I developed some pretty severe death anxiety because of it, but my mom was really good at handling it. She encouraged me to ask questions, and answered all of them openly and honestly. In hindsight I really appreciated this — being able to talk about what scared me really helped me overcome my anxieties. Playing super death-centric games like Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask helped in a similar way — by dealing with the subject hands-on I was able to confront my fears about my death and mortality.”

When DaRienzo first read about death positivity, a movement encouraging conversation around mortality and the end of life, the idea immediately resonated with her. She’s not the only one: buzz around her Mortuary Simulator prototype was so strong that she and Laundry Bear Games partner Andrew Carvalho decided to develop it into a full game, feedback for which has also been, according to DaRienzo, overwhelmingly positive. It speaks to the need we must have to interact — safely — with death, and the lack of appropriate venues to do so. A Mortician’s Tale is a chance to get intimate with the unknown and come out with some new experience points which, at least in this case, translate to real life.